Mary Fonsic Ran Away Again.

Exploring the newspaper articles that tell the story of her path to the Massachusetts School for the Feeble-Minded. Read the original version on the blog.

Read the original version on the blog. Many thanks to the Gloucester Lyceum, the Sawyer Free Library, and Community History Archive for digitizing these newspapers and making them freely accessible and searchable.

In 1900, Mary Fonsic was sixteen years old. She lived on Essex Avenue in Gloucester, Massachusetts with her mother, her stepfather, and her siblings, Maurice, Albertina, Anthony, and Carrie. She went to school, and she could read and write. Her mother, father, and step-father were all Portuguese immigrants. The family attended weekly Mass at St. Ann's church. And every day, a newspaper boy probably delivered a copy of the newspaper The Gloucester Daily Times to their front doorstep.

Newspapers in 1900 contained more than just "local news" as we think of it in 2024. Like Facebook today, it was also packed with weird advertisements, gossip, stories that were probably fake, police reports, and pictures from your aunt's friend's vacation to Nantucket. Mary's siblings would appear in the newspaper semi-regularly over the next 35 years. They reported on Maurice's lifelong involvement in local theater, as well as his surprisingly successful lawsuit against the City of Gloucester after he hit a city fire hydrant with his car. They wrote about the death of Carrie's daughter Lorena from the Spanish Flu, Albertina's 3(!) marriages, and Anthony's teenage job driving a horse-drawn carriage to deliver milk.

But Mary barely appears in the paper--except for obituaries, she is mentioned only during a short, 8-day period in August of 1900, shortly before she was admitted to the Massachusetts School for the Feeble-Minded.

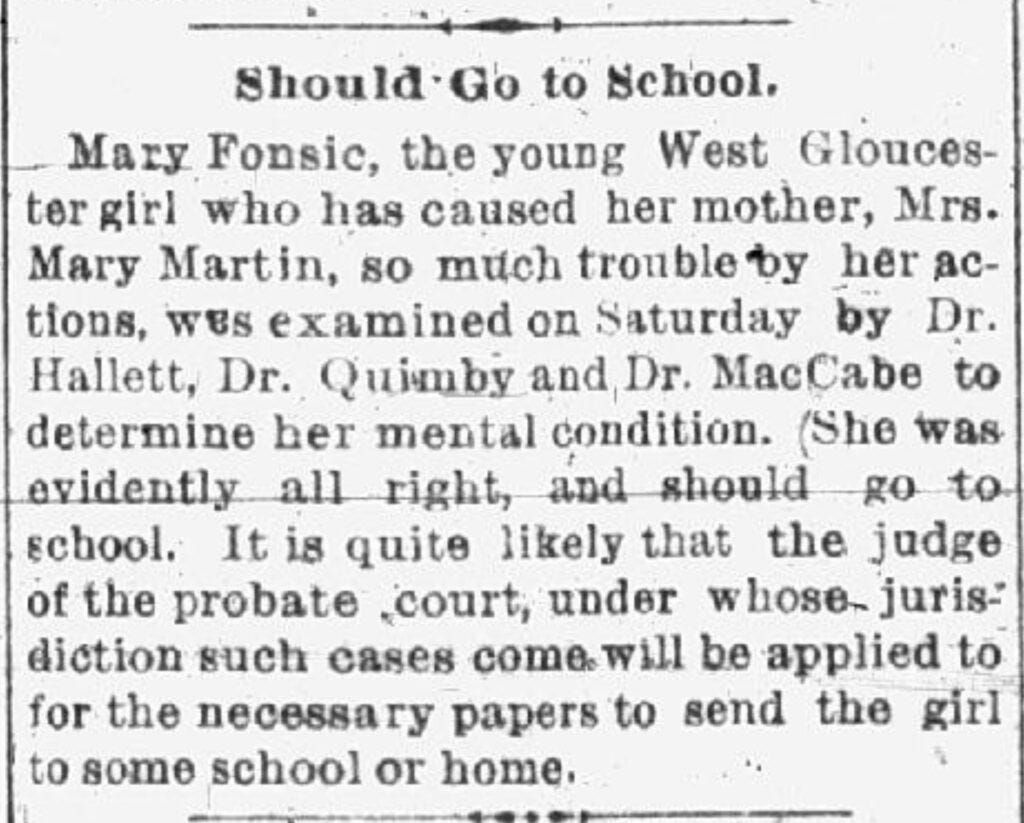

This first article appears on August 13th, 1900.

It's interesting to me that this first article suggests the reader knows that Mary has been causing “trouble”. The Times was a local newspaper, and Gloucester's population at the time was around 26,000. For context, my current local paper serves a population of 81,000, and the paper from the town I grew up in serves 100,000--yet I still often recognize names and faces. So, if the "trouble" Mary was causing was public enough, it would make sense for the newspaper to talk about her in this way.

The author doesn’t say what kind of “trouble”, though. What "actions" made her parents take her to the doctor? Whether the actions or symptoms she had were because of intellectual disability or some type of teenage rebellion is unknown. At the time, both could easily result in being sent to an institution.

Sending the girl to "some school or home" is also carefully phrased to avoid less comfortable words like "hospital", "insane", or "idiot". The concept of institutions in 1900 were still firmly rooted in the belief that people with intellectual disabilities could be "fixed" by education and moral teachings. And calling it a "school" also makes the rest of the family sound better--in 1900, as eugenics was beginning to become popular, having a family member institutionalized was shameful and meant that the rest of the family was morally or genetically weak.

Mary's mother, also, confusingly, named Mary, was clearly upset by the article. The following correction appears the next day:

Mary Martin's response, published August 14th, 1900.

Despite their sarcastic response to Mary Martin here, the Times did make a statement about the physician's findings (see their previous article).

Mrs. Martin's response gives us some new information about the situation. It seems important to Mrs. Martin that the public understand that the doctors found her daughter to be feeble-minded (intellectually disabled). My best guess here is that she wanted her neighbors to understand that she wasn't sending her daughter away for convenience--her daughter really did have a condition which required "medical attention" and that she would be receiving "good care". Whether Mary Martin was a woman who cared deeply about her daughter's well being, her own public image, or both, we will honestly never know.

The final article about Mary is published one week later.

Published in the Gloucester Daily Times, August 21st, 1900.

Finally, some clues about Mary's behavior that likely prompted the doctor's visit. A "mania for running away" suggests that this has been an ongoing problem. Now, of course there are many reasons that 16 year old girls run away from home unrelated to intellectual disability, and that's certainly possible here. But to me, this sounds more similar to the wanderings of Hugh Blair than a rebellious teenager. She wasn't found with friends or a boyfriend, and she wasn't at a train station or bus depot trying to leave town. She travelled less than two miles in fifteen hours, walking from West Gloucester, where her family had recently moved, to Main Street in Gloucester, the neighborhood she had lived in for most of her life.

This is the last we hear about Mary in the paper. Maybe it was shortly after this adventure that she was sent to the Massachusetts School for Idiotic & Feeble-Minded Youth, later renamed the Walter E. Fernald State School, where she would spend the rest of her life. Or perhaps there were more incidents like these that simply were not interesting enough to make the daily paper. But by 1910, the census records her as an "inmate".

Soon, I want to share more about what we can infer about Mary's life--details from Fernald and places like it, how institutions like Fernald changed over the early 20th century, and what life was like there. I have some pretty interesting primary sources, and I'm working to track down more.