What is the difference between Autism and Intellectual Disability?

Plain Language Version

Original version here!

Autism and Intellectual Disability are not the same. But the two diagnoses share a deep history. This shared history is important and reveals the origin of many beliefs, misconceptions, and prejudices about Autistic people and people with Intellectual Disabilities (ID). Here, I'll provide a brief overview of that history. Many of the events and topics covered here I'll come back to for a deeper exploration later; I'll try to provide updated links as I go.

I'll also provide some short descriptions of (fictional) people who are Autistic, have an ID, or both. My goal is to show the similarities and differences between Autism and ID, although I am not a clinician and cannot diagnose anyone, real or fictional.

A short history of I.D. & Autism

Intellectual disability has gone by many names, and I haven’t been able to find a "first" record of someone with an intellectual disability. Many historical words for intellectual disability, such as "idiot" or "moron", developed from 19th century clinical definitions into petty insults. Other past clinical words are now slurs (the R word, for example). Intellectual disability has always existed and been known about.

Autism is a more recently understood difference in the way people think. Since it was first defined, Autism has had many very different definitions. In the 40's, when Leo Kanner first "discovered" it, Autism was thought to be a very rare disorder that caused difficulty connecting with other people and a narrow set of skills and interests. This quickly changed.

20th Century Autism

From the 1960s through the early 2000s, people proposed many different theories about Autism, and the types of services provided to Autistic people changed a lot. At first, doctors guessed that around 1 in 2500 people had Autism. Over time, doctors realized Autism was more common—now, some people think as many as 1 in 63 people may be Autistic. There are a lot of reasons for this. One is that parents who had a child with in intellectual disability might have wanted their child to be diagnosed with Autism. Starting in the 1975, public schools were required to allow children with intellectual disabilities to go to school. However, the school only had to offer an education “appropriate” to each student’s needs. For kids with an ID, this often meant their education was not very good. Schools could argue that “well, these kids will never be able to get a job anyway, so they don’t need to know much”. During this time, there was also a big increase in research on Autism, and especially on how to “cure” Autism or “improve symptoms” of Autism. This research developed therapies such as Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA) and Facilitated Communication (FC). Having these types of therapies available meant that Autistic kids might get more resources at school than kids with just an intellectual disabilities, since there was hope that they would “get better”.

Importantly, during this time period, it was estimated that 75-80% of Autistic people also had an intellectual disability. Autism was different from intellectual disability, but it was also an important way for people with ID to gain access to resources. As a result, the cultural definitions of Autism and ID became connected. Growing up in the early 2000's, even though I knew many people with Autism and/or ID, I didn't understand that there was a real difference. It felt to me like "Autism" was a polite way to say "intellectually disabled". Autism was something to say proudly; Intellectual Disability was something to whisper apologetically1.

Autism & Intellectual Disability Today

While the amount of people being diagnosed with an ID hasn’t changed much in the past 50 years, more and more people are being diagnosed with Autism. That means that there are more and more people who have Autism but don’t have an ID. Advocacy for Autism, and particularly advocacy led by Autistic people, is becoming more well-known. Even though many advocates for and with intellectual disabilities are working hard, the movement is still not well-known.

Right now, I’m sitting and writing at a public library, which is a good place to see the way the difference in successful advocacy impacts the availability of resources. In this library, there are currently 28 books on the shelf about Autism, and 1 about Intellectual Disability (and that's being generous--the single book about ID was specifically about Down Syndrome, not ID as a whole).

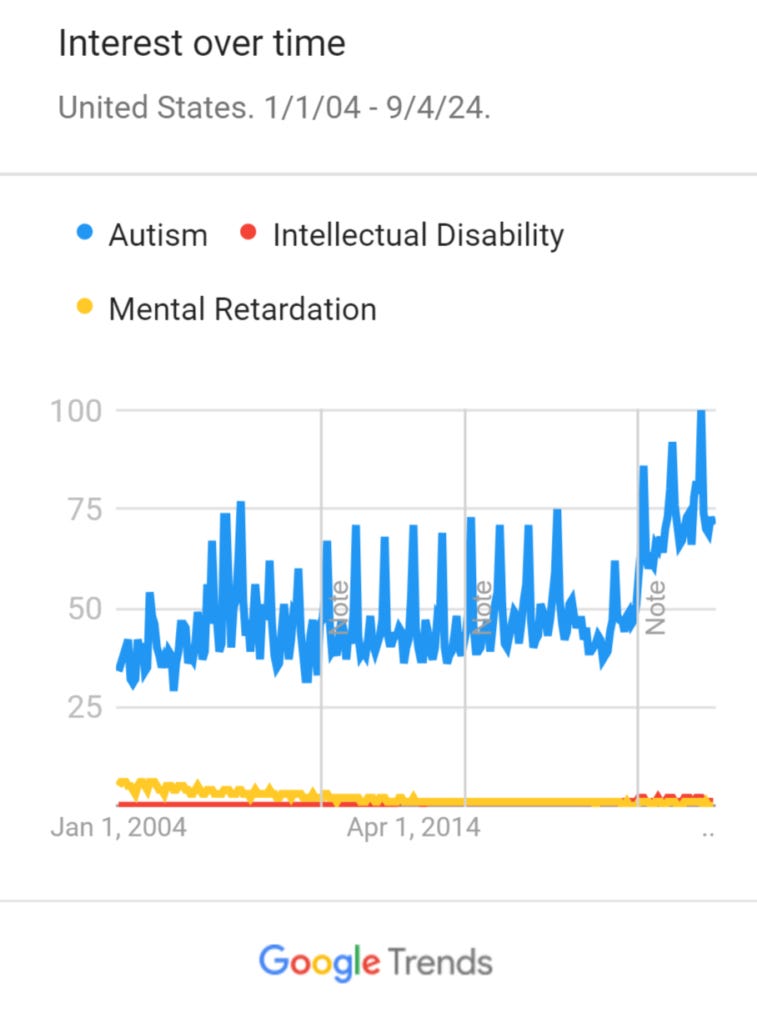

We can see this in Google Trends too. Here's a search I just ran. Note that I included the R word in the search because before 2010, it was still used in government documents, and I think it's important for understanding the data.

From this data, we can see that even in 2004, searches for Autism far outpaced searches for Intellectual Disability, despite their similar diagnosis rates at the time. Autism was searched 6-7 times more frequently than Intellectual Disability. Now, in 2024, that gap has grown even wider--Autism is searched 70 times more frequently than Intellectual disability. Given that Autism diagnoses today are 3 times more common than I.D. diagnoses, we might expect the gap to multiply by 3. Instead, we see a 10 times increase.

Are these trends a problem?

I want to be very clear that I think that increased rates of Autism diagnosis is a good thing. Given the way the diagnosis has changed over time, I don't think we're seeing an increase in people who fit the diagnostic criteria for Autism, I think we're seeing an increase of people who fit the criteria for Autism seeking a diagnosis. I know multiple people who have been diagnosed with Autism as adults, and it has improved their lives. Everyone deserves to receive access to resources that help them live better lives, and everyone deserves to feel understood.

The gap in advocacy is concerning to me though, particularly as spaces for Autistic people change. In the early 2000's, advocacy for Autism was closely tied to advocacy for people with intellectual disabilities. Now, they appear to be separating. I worry that spaces that were historically inclusive to people with ID will become hostile. And I worry that, in some scenarios, Autistic people without an ID will encourage the widening of this gap to avoid the stigma associated with intellectual disability.

Although my perspective slightly differs from the author, I do recommend checking out this article, which illustrates these concerns well.

So, what do Autism & Intellectual Disability look like?

Autism and Intellectual disability can co-occur or occur separately. People with either diagnosis can require widely varying levels of support. Here, I offer brief examples of what people with different combinations of diagnoses and support needs might be like. All characters are fictitious and any resemblance to real people is coincidental, although I did do my best to represent real-world experiences of disabled people in this characters.

Iris

Iris has an intellectual disability, and she is not Autistic. She has relatively low support needs and lives in an apartment by herself. She doesn't drive, but she has a supportive social network who frequently offer her rides. If no one is around to drive her, she can order an Uber. She has a job as a receptionist at the YMCA, and she enjoys getting to chat with the patrons. She likes cooking, but has a hard time learning new recipes. Family members and friends regularly check in to see how she's doing and help her do more complicated self-care tasks like making doctors appointments and paying her bills.

Evan

Evan has an intellectual disability, and he is not Autistic. He has relatively high support needs. He lives with his parents, but he hopes that soon he will be able to move into a group home with other disabled people. His friends and siblings love when he takes them on walks around his neighborhood, but if he goes by himself, he often gets lost. He helps around the house by setting the table for dinner, feeding his cat Petunia, and sweeping the floor. Evan doesn't have a job, and gets a disability check each month. He loves playing on his Special Olympics basketball team.

Rohan

Rohan has an intellectual disability and he is autistic. He has relatively low support needs. He lives with his girlfriend. Most of the time, he takes the bus to get around, but it's very frustrating to him when the bus is late. Right now, he's trying to get a job, but having a hard time. Even though he has an associate's degree in IT along with several other advanced certifications, he struggles during job interviews. He loves cooking and knows all the science behind it, and in his free time, he's always experimenting in the kitchen. He hates eating food prepared by other people, and his girlfriend hates cooking, so this works out well for them. She takes care of some of the self care tasks he struggles more with, like doing the laundry.

Michael

Michael is autistic, has an intellectual disability, and has relatively high support needs. Since his mother passed away, he has lived with his aunt. He is nonverbal and needs full-time care. Michael doesn't usually respond when spoken to, although he does hear and understand what people are saying. He engages in self-injurious repetitive behaviors, like hitting his head against a wall. During the day, he goes to an adult day programming center. He likes playing bingo and making art there. He wishes he had more friends his own age.

Vanessa

Vanessa is autistic and doesn't have an intellectual disability. She has relatively low support needs. She lives in student housing at the university where she goes to school. She's currently pursuing a PhD in Public Health, with the ultimate goal of becoming a professor. She rides a bike as her main form of transportation. In her spare time, she operates an Etsy shop selling paintings of characters from her favorite TV shows. Vanessa has a tight-knit group of friends outside of school, but her classmates see her as somewhat anti-social and awkward, because she never attends the informal student-faculty gatherings. She doesn't feel comfortable telling them it's because the noise in the room they hold the events echoes a lot, the smell of the alcohol bothers her, and she doesn't like making small talk.

Kylie

Kylie is autistic, she doesn't have an intellectual disability, and she has higher support needs. She is non-verbal and uses an AAC (Augmentative and Alternative Communication) device to communicate. She lives with an in-home support aide named Lisa who helps her cook, clean, and shower. Kylie doesn't leave home often, because she is very easily overstimulated, and can become a danger to herself and others when trying to escape that stimulation. She spends lots of time on the internet chatting with friends. A few days a week, either one of her siblings or a respite worker will come spend time with her to give Lisa a break. Her favorite activity is dancing.

Final Takeaways

People who are autistic or who have intellectual disabilities have a very wide-ranging set of challenges and support needs; these examples don't even begin to cover it. I'm not a clinician or someone involved in specific policies around services for people with disabilities. I'm simply a friend and family member of many people who have these disabilities. Please let me know if I misrepresented anything above; I've done my best to make it accurate to people's real-life experiences. I think it's important to talk about the specific challenges that people with intellectual disabilities face, and it seems like many people (outside of those who have direct, regular contact with people who have intellectual disabilities) are afraid to talk about these specific challenges.

Understanding the terminology and specific differences between Autism and ID is also important for some upcoming, more history-focused posts I have coming up. Subscribe to the substack to be notified for my next post, which will be about 18th century Scottish Laird Hugh Blair of Borgue!